The evolution of stories has always fascinated me.

Long before anything was written down, stories were told in groups, around fires at night. Nobody knows who started it or why, but stories were very much a community effort. Each new storyteller would put something of themselves into the tale. Bits were added and taken away. There are some stories which stretch on for hours with episode after episode, and others where it seems the storyteller suddenly remembered they had to be somewhere else, and the action ends in a rush.

As people travelled from place to place, they took their stories with them. Take Cinderella, as a well-known example. The glass-slippered version we know best comes from Charles Perrault in 1697, but the hunt for footwear first appears in an ancient Greek tale of a slave girl who married a king. Then there’s the English tale of Tattercoat, the Chinese story of a girl who receives supernatural help and gold shoes from the bones of a dead fish, and the Brothers Grimm version in which the ugly sisters’ eyes are pecked out by birds as punishment. And hundreds more.

Over time, many of these stories were written down and took the step out of the oral tradition into literature. Which brings me to the Mabinogion and Lady Charlotte Guest. Born in 1812, she was a keen student of language and literature and when she married the MP for Merthyr Tydfil and moved to Wales, she became fascinated with a collection of Welsh tales, which she called the Mabinogion. Her translation became the definitive English-language version for over a century.

The Mabinogion itself is a strange beast. There are four main ‘branches’ – collections of tales which weaved in and out of one another. Following these, are four independent tales, and three romances.

Over the years, there have been many translations, retellings and spin-off stories, the most famous probably being Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain, which draws from a lot of Welsh myth including elements of the Mabinogion, and Alex Garner’s The Owl Service, which uses the story of Blodeuwydd. There’s also a wonderful reworking in verse by Matthew Frances and a series: New Stories from the Mabinogion from Welsh publisher Seren, which bring the stories up to date with contemporary and futuristic settings. And there are many, many more.

Surely we don’t need any more versions, you might say. I find myself oddly split here, because I have a livid dislike of screen adaptations that mess with my favourite books. But the ancient tales collected in the Mabinogion were in the public domain long before they were ever pinned to a single version on the page. They draw us back to a time when storytelling was a community effort, when anyone and everyone could throw in an idea and see what happened.

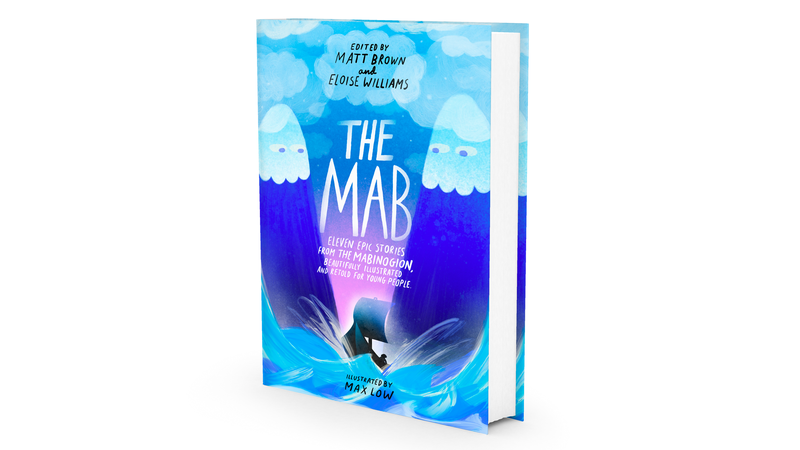

So I was delighted when the hilarious Matt Brown asked if I’d be interested in taking part in a new, collaborative version of the Mabinogion for children. I’d already rewritten several of the stories for my book of Welsh folktales coming out next year (available for pre-order now, shameless plug) and I was keen to do more. The more I learned about The Mab project, the more excited I became. Eloise Williams was co-editing. PG Bell and Sophie Anderson were also contributing, along with a load more huge names in Welsh literature. Each story would be told in English and Welsh. And the whole thing would be illustrated by Max Low, who is funny and generous and altogether awesome. If you don’t believe me, look at this cover.

But the best thing of all? This is a community effort. Publication will depend on the support of readers. Pop along to Unbound and see the range of rewards on offer. You can get anything from a single copy to a school or bookshop package including an author visit. All supporters will have their name listed in the book, because without you the book will not exist.

To quote myself from The Accidental Pirates – there are three kinds of people in the world: those who listen to stories, those who tell them and those who make them. Be a story maker. Let’s bring this book to life.